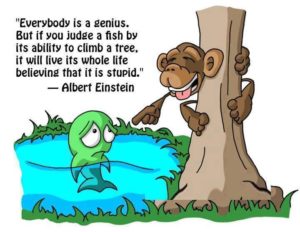

For many years, the quote you see on the left has been burned into my mind. Every time I participate in a conversation about our state’s accountability system, it dominates my thoughts.

For many years, the quote you see on the left has been burned into my mind. Every time I participate in a conversation about our state’s accountability system, it dominates my thoughts.

Today, I attended the third meeting of the Governor’s ESSA Advisory Council. The council has been working in subgroups related to Standards, Assessments, Accountability, Teacher Preparation and Evaluation, Early Childhood and Finance. During the accountability presentation, and again during the evaluation presentation, a spirited conversation took place regarding the invalidity of the current accountability system and ways to improve it that would make the resulting data more meaningful. What reporter Will Sentell, of the Baton Rouge Advocate, got out of this conversation is that the council opposes expecting students to reach “mastery,” and wants to lower expectations. He took to Twitter with his incorrect interpretation which prompted many of the staunch supporters of education reform and invalid measures of accountability to chime in.

As shown in the image on the right, they often engage in ridicule and are aghast at the inaccurate absurdities. This is a textbook example of Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals (See Rule #5), which are often confused with the Communist Rules for Revolution. Alinsky’s rules were intended to help organized communities combat an overbearing government. There is a certain irony in the fact that all of the reformers utilize these tactics. I’ll be frank, when I see comments like these from self-appointed experts on what is best for children, it infuriates me. But, that is what they want. It is how their game works. I will be brief so that you can get to the part that matters.

As shown in the image on the right, they often engage in ridicule and are aghast at the inaccurate absurdities. This is a textbook example of Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals (See Rule #5), which are often confused with the Communist Rules for Revolution. Alinsky’s rules were intended to help organized communities combat an overbearing government. There is a certain irony in the fact that all of the reformers utilize these tactics. I’ll be frank, when I see comments like these from self-appointed experts on what is best for children, it infuriates me. But, that is what they want. It is how their game works. I will be brief so that you can get to the part that matters.

Our accountability system, under the guidance of Supt. John White, has “raised the bar” for what our students are expected to achieve. What does that mean? In a nutshell, it sets an inappropriate level of achievement for ALL students to attain, then labels students, teachers who teach them, and schools that enroll them, as failures when they don’t reach the goal. This includes students who enter a classroom two, three, even four years behind their grade level. Not only are they labeled as failures, but there is no acknowledgement of the real progress that is being made by these students. Essentially, teachers who serve “at risk” students are required to be infinitely more “effective” than those who don’t…in one year. It is a pretty shocking expectation from organizations that claim a goal of serving the less privileged and closing the gap.

Below, you will find a letter from the parent of a child who attends LA Key Academy (LAKA); a charter school that serves students with dyslexia. Recently, while Supt. White was recommending an extension on LAKA’s probationary period for poor performance, which violates BESE policy, while simultaneously revoking two charters for the same reasons. In my last blog, I illustrated how the students of LAKA are being served exceptionally well, while the accountability system reflects; otherwise. Please take time to read this parent’s story.

My story is simple. I am not a medical doctor or a PhD. I am a Mom who is here to help explain the daily challenges of my nine (9) year old child who struggles with dyslexia with the hope to bring awareness for every child with it (whether diagnosed or undiagnosed).

Dyslexia often prohibits my son from having the ability to match sounds with the alphabet. This impacts his reading, spelling and speaking. It is not a sign of poor intelligence or laziness. In fact, my son is exceptionally bright and intuitive, creative and very tender hearted and loving.

My son attended daycare and then went to Pre-K at four (4) years old. At five (5), he started Kindergarten at a private school. About halfway through his Kindergarten year, I noticed that he was unable to do some things that other children did. Most things were harder for him than other children. He would write several letters backwards, which the teachers said was normal at this age. In addition, he could not understand the concept of rhyming. We would practice every day, played games with it, and even rhymed in the car. Yet, he still was unable to do it. I would say the word “cat”. Where other children would rush to say bat, mat, or sat, my son would say “tab”. He would only hear the last syllable and start the next word with that. He read at a very slow pace and would have to sound out every letter in the word, often being unable to hear them when he said them together. If I sounded them out loud, he would occasionally be able to blend them and make the correct word. I was concerned at the end of the school year and met with his teacher. She assured me that there was no need to worry. That he was a boy and boys tend to take a little longer to read but he would get it on his own time.

I decided, on my own, to place him in a reading program through Louisiana State University over the summer between his Kindergarten year and First grade. It was a six (6) week program geared to make stronger readers. He was assessed after two weeks in the class and placed in the lower reading group. We continued to work and he did not improve much, if any. I met with this teacher and she assured me that he was trying and would get it on his own time.

He started first grade. The first two weeks were great, then, the real trouble started. The frustration and anxiety increased tremendously with him. His twenty (20) minutes of homework would easily turn into two (2) hours. He brought home a worksheet with sentences to read every night. One sentence would take us up to five (5) or six (6) minutes instead of a few seconds. It was very hard to find the patience to listen to him sound out letters and then try and blend them into a word. If he would have trouble with a word in a sentence that wasn’t easily sounded out, I would help him with it. When the next sentence contained the same word, he acted as if he had never seen the word before in his life. I would get frustrated and explain to him that he just read it no more than ten (10) words earlier. I could not understand why he was unable to see that was the same word and just say it. This led to crying (on both of our parts), each and every night, from the time we started homework until the time that he went to bed. At an appointment with his teacher in early September, she assured me that he was a boy and boys took longer to read sometimes but he should have it by Christmas.

In the middle of October, his teacher asked to meet with me. She stated that she was seeing some red flags and asked if I was open to having him tested. She was very honest that she did not have a degree to assess him but he was showing some signs that had caused her some concern. I went through my insurance company and made an appointment with a local doctor for the end of October. The doctor was not at the office for my appointment, yet spoke to me through Skype. His assistant ran some tests on my child. In mid-November, I returned for the results. I still was unable to meet the doctor, yet, my son was given a generic diagnosis of dysgraphia from the handwriting samples that I provided from school.

I contacted my insurance company and they said that it would be June before I could get in to see anyone else. Frustrated, I didn’t know what to do next. Every minute I spent not getting help for my son, was a minute that he was falling further and further behind. Completely distraught, I decided to have him tested at a psychological facility and pay for the testing out of pocket. He was tested at the end of December 2011, by a PhD, who actually met with my son and me in person. In the middle of January 2012, my son was given the diagnosis of Dyslexia and Developmental Coordination Disorder. It was recommended that he start speech and occupational therapy. We also started with a tutor three times a week for help in reading.

I received the report at the end of February and met with the school at the beginning of March 2012. By this date, my son had already failed for the year because if a first grader fails reading, he fails the year. We made his IEP for the next school year. It consisted of testing in another room, having everything read to him except his reading test, and he started seeing the Reading Interventionist every day at school.

My son would come home every day and cry and ask, “Mom, why am I stupid and no one else is”? How, as a parent, do you look into your seven (7) year olds eyes, and reassure him that he isn’t stupid but that his brain just acts a little different from everyone else’s? His self-esteem plummeted. He would never read a book out loud to anyone but me. He became very introverted and never wanted to do anything outside of the house.

The next school year, August 2012, he started first grade again. His grades were much stronger this year. He maintained an A/B average with an occasional C; however, reading was still in the low B’s. He was having occupational therapy a few times a week after school. He had speech therapy once a week after school. He was meeting the Reading Interventionist every day at school for thirty (30) minutes and he was still being tutored three times a week after school. I met with the interventionist towards the end of the school year and she told me that she saw only the slightest improvement with his reading, although she would have expected it to be a little more since she worked with him every day.

At this point, I was dumbfounded that I was paying thousands of dollars in tuition and this school really didn’t have the resources to help my child. It wasn’t that they didn’t try to compensate for his needs; however, my child didn’t fit into the “normal” mold of students in his class. The school was not going to change their teaching habits for one child. So, they tried to mold my child to learn like every other student although it was impossible for him.

On May 23, 2013, I found out about a new school that was being started in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. It was a charter school for dyslexic students. I immediately contacted them to see how I could apply. To qualify, the child had to have a type of dyslexia or reading issue with an evaluation to support it. Since my son was previously diagnosed, I applied and my son was accepted. I honestly had some reservation because I was very unsure what to expect. In addition, he had to make new friends just the year before and he was already so introverted and now I was making him make new friends all over again.

In August 2013, my son started at Louisiana Key Academy. A few days into the school year, he came home and was excited to talk to me because he found out that a boy in his class had trouble reading, too, and so did a girl in his class. For the first time in his life, he didn’t feel like something was wrong with him because everyone in this school was just like him. His self-esteem picked up a little each day.

In addition to feeling like he belonged for the first time, the classroom size was dramatically different than we had previously experienced. He went from a classroom of 32 (thirty-two) children, at the prior school, to a classroom size of 16 (sixteen). During reading, his class size dropped to 6 (six) children. He was able to get individual attention while also learning from the other children in his group.

Louisiana Key Academy uses a systematic evidence based curriculum called Neuhaus. The teachers and reading interventionists are trained to teach this evidence base curriculum. The more knowledge he gained through the Neuhaus program about how letters work to from words, the higher he held his head. He stopped referring to himself as “stupid”!

The pivotal point in this journey with my son happened around January of this year. I was helping my other son, who is seven (7) with his homework while my son, now nine (9), with dyslexia was sitting at the table working on homework, too. My seven (7) year old was having some trouble with a word and my nine (9) year old jumped up and said, “If it is a vcv, you slice the E and put a macron over the first v”. I looked a little confused and he looked at me and said, “Macron means that you make it long, Mom”. I immediately pointed to another word and he explained that one to me too. I told him how proud I was of him and he said, “It is easy now that I understand how to decode words. “It makes sense now Mom.”

At the end of last school year, my son had a project where he had to be a famous American. Each child dressed as the person and had to present an oral report. My son chose Steve Jobs. While my son chose Mr. Jobs because he loves video games and Mr. Jobs created my son’s favorite way to play them, we learned that Mr. Jobs was dyslexic. We were able to use his report as a way to show each child in his class that they can succeed – it just takes hard work and dedication. As I held my breath, my son stood before his entire class and their parents and read his report out loud (Something that he has never done – EVER).

With all the programs and options that I have tried, I finally see something that is working for my child and I cannot express the gratitude that I feel. Although my son has overcome so much, he still has daily hurdles that he must conquer. My son still has anxiety about school and some social settings and probably always will. He cries occasionally when he wakes up and knows that it is a school day. He continues to be a poor speller and, at times, he still has difficulty getting words out. However, he finds the strength to push through each challenge and succeed.

Reading difficulties are the most common cause of academic failure or underachievement in our society. An inability to read affects every aspect of a person’s life. Luckily, for my son, I have been vigilant in trying to find a program that will help my child succeed, as I am sure every parent here today would do. In my opinion, early identification is the key. The longer we wait for a child to be diagnosed, the more valuable time is wasted that could be helping children before they fall further and further behind. Smaller groups and class sizes are invaluable, especially for the children who do not fit the standard learning “mold”. I also feel that children need to around other children who struggle the same way that they do they don’t feel ostracized and have lower self-esteem. One thing that each of us need to remember is that our children are the future. We might not have a cure for dyslexia, but together, we can find a solution.

Well, at least you “got it”, Ganey. There will much “sound and fury” from the “self-appointed” as you called them. The Governor’s Advisory Council members are not yet finished with considerations but we are approaching the topics from a position of “been there and have done it”. All the members have in some capacity or other worked with students and understand that static models of achievement do not tell the story of a child’s growth. It is time that the real story of the great things that teachers do each and every day is finally told. Thank you for being a thoughtful and analytical voice for common sense education improvements.