Last week at this time, teachers across the United States were beginning to receive small tokens of appreciation from their students for “Teacher Appreciation Week.” I have been teaching for 15 years. All of those years have been spent in a special education classroom. My roster of students is generally small, and I am accustom to not being showered with gifts like my peers who work in the regular education classroom. I have taught at every grade level from kindergarten to 12th grade. I can count on one hand the number of gifts I have received during Teacher Appreciation Week. All of them chosen by a caring parent, and I am appreciative of their kindness. Last Monday, I received my first ever gift of appreciation from a student; not a parent. It was probably the most meaningful gift I have ever received, or ever will. I received a handwritten letter.

Last week at this time, teachers across the United States were beginning to receive small tokens of appreciation from their students for “Teacher Appreciation Week.” I have been teaching for 15 years. All of those years have been spent in a special education classroom. My roster of students is generally small, and I am accustom to not being showered with gifts like my peers who work in the regular education classroom. I have taught at every grade level from kindergarten to 12th grade. I can count on one hand the number of gifts I have received during Teacher Appreciation Week. All of them chosen by a caring parent, and I am appreciative of their kindness. Last Monday, I received my first ever gift of appreciation from a student; not a parent. It was probably the most meaningful gift I have ever received, or ever will. I received a handwritten letter.

Now, I want to establish a disclaimer. Many of my coworkers, particularly in the Language department, assign their students the task of writing a letter of appreciation to a teacher. This student could have chosen to write to any one of her six teachers, but she chose to write to me.

This particular student not only struggles to navigate the social norms faced by all teenagers, but also fights for personal space and identity in a very large family, and has to climb over a multitude of other barriers outside the confines of the classroom. In addition, about 1/3 of the way into the school year, she suffered a physical injury that left her unable to work at the job she was so happy to get.

I was so moved by how she expressed her appreciation for what I have helped her do, what she has learned, and how she plans to apply that to her future, I felt compelled to return the favor and give her a handwritten “thank you” note.

When she came to class that afternoon, I handed her the note. Smiling from ear to ear, she opened it, stared at it for a moment, then looked at me. “Mr. Arsement. I don’t think I can read this.”

Slightly embarrassed, I quickly responded, “I’m sorry. The medicine I take makes my hands shake. Would you like me to type it?”

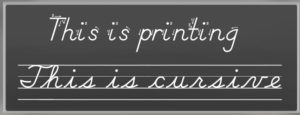

She laughed. “I can’t read cursive,” she said. “But I’ll try.”

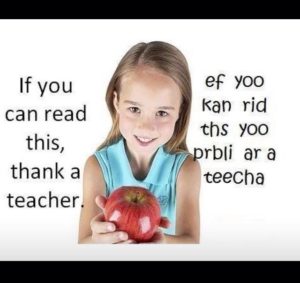

For a week, I have been moved by the heartfelt message she gave me, but also obsessed with the fact that she couldn’t read my response. I have written on this topic, before, and two years ago a bill was authored and passed by Senator Beth Mizell requiring that cursive be taught in 3rd grade. While I’m not a fan of legislating curriculum, I can appreciate the need for cursive being taught, but the fact remains that in grades K-2, there are no requirements that print writing be taught. Learning to print is not only a vital part of learning to read, but also contributes to development of fine motor skills.

For a week, I have been moved by the heartfelt message she gave me, but also obsessed with the fact that she couldn’t read my response. I have written on this topic, before, and two years ago a bill was authored and passed by Senator Beth Mizell requiring that cursive be taught in 3rd grade. While I’m not a fan of legislating curriculum, I can appreciate the need for cursive being taught, but the fact remains that in grades K-2, there are no requirements that print writing be taught. Learning to print is not only a vital part of learning to read, but also contributes to development of fine motor skills.

There are a multitude of other vital skills that should be taught during the early education years, but they are not. I know they are important skills, and that by not teaching them, we are robbing children of the very foundation their education should be built upon. Any teacher who knows anything about the theory of learning knows this. So, why are we doing it?

I, for one, have said over and over again that education reform has facilitated change that doesn’t improve outcomes, but instead, results in “education deform.” Here are just a few examples.

- We don’t teach phonemes, or phonetics, but we expect children to know words by sight or be able to sound them out when they don’t.

- We don’t teach basic numeration, or require memorization of Math facts or algorithms to facilitate quick problem solving, but instead, expect them to use multi-step, time-consuming methods.

- In the absence of memory building skills, we expect children to follow multi-step directions.

- When students don’t perform well in reading comprehension which requires drawing from background knowledge, inference, and the use of virtually all higher order thinking skills, we reduce the expectation to citing specific text which requires little thinking. (Read more about that, here.)

I consider myself a problem solver and a thinker. It’s not what I was taught to do, but expected to do. I’ve learned it by reading, exploring and thinking critically. In trying to look past the problems of ed reform, and the specific causes of these problems, I’ve tried to determine what the underlying reason is for the belief that these reforms have value. I believe that ed reforms are largely driven by political ideology, but the vehicles used to achieve reform are cultural norms that are contrary to educational norms. Here are a few that I have come up with.

- Instant gratification: The culture that our children are growing up in does not understand the value of patience or slow and steady progress. We live in a world that allows us to get whatever we want; when we want it. As a child, I patiently waited for a week to watch the next episode on my favorite shows. Today, we have NetFlix. When NetFlix releases a new season of their original series’, my family watches the entire season in two nights.

- No appreciation for what is old: There’s an increasing belief that doing something “the old way” should be frowned upon. The only way I will ever accept someone saying this is if they completely understand the how and why of the old way, and their goal is to improve upon it. To discount the old way because you don’t understand it, is unacceptable. My grandmother made the best okra gumbo. She used okra that she prepared in a special way, well in advance. Out of five children and nineteen grandchildren, there are only two of us that know how to do it the way she did because we took the time to learn.

- The quest for how and what, but never why: This is a phenomenon that I see in nearly every aspect of life as we increasingly change how or what we do because we don’t understand why. As a musician, I have spent a lifetime learning, and unlearning, the instruments I play and trying to understand why we play music the way we do. In each of the instruments that I play, there are about a 1/2 dozen, or so, embellishments that you can find in nearly every song. They add ornamentation to the basic melody and give songs personality. It is so frustrating to see young players with no interest in the history, or background, and focus entirely on the embellishments and transform beautiful melodies into never ending embellishments. We see this in the tests that we use to measure achievement and in the curricula we use to teach to the test. We see this in employment trends requiring employees with task-specific skills. There is no need for critical thinking in the modern workplace.

These are things that weigh on my mind, everyday. I wonder if we will ever reach a point in which we collectively recognize the damage we are doing to our children and their futures. We live in a country that has dominated the sciences, has led the way in space travel, and has made enormous advancements in healthcare. I fear that the very skills that have allowed us to make technological advances have resulted in technologies that essentially make those skills unnecessary. The percentage of matriculating students who are capable of history making discoveries will dwindle with each generation. Will the students of the future appreciate their teachers? Will the time come that we will look back and ask, “What have we done?”